April 2020 | 1744 words | 6-minute read

In his final year of an MBA course at Pune’s Symbiosis Institute, Suyog Shanbag developed an app that mapped the city’s 1,600 schools by location and performance. This open-data platform enables citizens to choose a school based on proximity, facilities, its teacher-child ratio and the like.

Extend the idea to a range of other civic services and it becomes an education to understand why and how the platform is being put to pointed use by the Pune Municipal Corporation (PMC).

Pune Open Data Store, as the platform is called, was born out of the Maharashtra government’s open-data policy, which calls for making data collected by municipal bodies available for the public good. The PMC portal is a manifestation of that idea, offering citizens access to 475 data sets that cover water, sewage, traffic, property tax and much more. The objective is to use the data to improve civic services while also generating business opportunities.

The platform is part of the Tata Trusts’ data-driven governance programme, which supports evidence-based civic planning and helps administrations cement innovative data policies. That means simplifying for citizens the once-arduous task of tapping the information they need.

The Pune project has evolved from a 2016 initiative where the Trusts surveyed the data capabilities of eight Indian cities on aspects such as air and water quality, infrastructure, green cover, schools and hospitals to determine how urban administrations could utilise data in policy planning and decision making.

Pune was ranked first in the survey, followed by Surat and Jamshedpur, and won itself a platinum rating. Pune is also part of the India government’s ‘smart cities mission’ and home to an entrenched technology ecosystem. This combination of factors made it a magnet for the Trusts and their data-driven governance initiative.

It began with the Trusts partnering PMC in a pilot project with the big-picture target of fostering an open-data culture. It became clear soon that for the project to have legs, a dedicated resource was necessary onsite, someone who could assist with processes and protocols, advocate the need for freely available data and support the administration in ensuring data transparency.

“We realised that advocacy and support at the local level are necessary to boost data-based government service delivery,” says Shruti Parija, who heads the Pune initiative and is a programme officer with the Trusts. That led to PMC and the Trusts picking a ‘city data officer’ (CDO) — a first for India — and the job went to Anita Kane.

On deputation from Tata Consultancy Services, Ms Kane came on board knowing she would be breaking new ground as there was no clear roadmap of the way forward. PMC did have an open-data platform back then but it was sparsely populated. A trickier challenge lay in working with, and through, the corporation’s hierarchies and convincing its 60-plus departments to collaborate.

Standardised quality

Each department had a different format of collecting and storing data. “Mining data to get qualitative insights requires that they be standardised and of good quality,” explains Ms Parija. “Also, data was often entered manually and that meant errors creeping in either at source, or during the digitisation exercise. This was a difficulty that had to be tackled.”

The privacy of users was another critical piece. Data published on the open platform had to be screened to ensure that personal information was stored securely. Consequently, this placed a restriction on the kind of data sets that could be published.

That the initiative took off and gathered momentum in spite of the roadblocks is in no small measure due to the strong support it has received from PMC, particularly commissioner Kunal Kumar and Rahul Jagtap, head of its IT department.

Problems persist two years into the current phase of the project, but Pune city has woken up and smelt the potential of data-based solutions, not to mention the business opportunities offered by the platform. Mr Jagtap, who has taken over as CDO from Ms Kane, says the platform has had a ripple effect, with the initial reticence of PMC’s employees and departments giving way to openness on data.

Significant here, adds Mr Jagtap, is the potential to pull in additional revenue. “We now have data on land records, on building permits that have been issued for construction, and on property tax being paid at an individual level. If we can correlate these three sets of data, we can check whether citizens are paying the right quantum of tax.”

For now it’s all about delivering data to citizens on everyday services: analysing bus routes to make peak commuter travel smoother and faster; gauging the water quality in rivers to determine pollution sources; and figuring out where new schools and hospitals are needed. There are a plethora of subjects and issues on which the data platform seeks to inform and enlighten.

The Trusts realised early in the project that it was essential to spark public interest in the resource being provided. “Merely uploading data on the open platform is not enough,” says Ms Kane. “It has to be analysed to generate actionable insights and this requires immense effort and qualified personnel.”

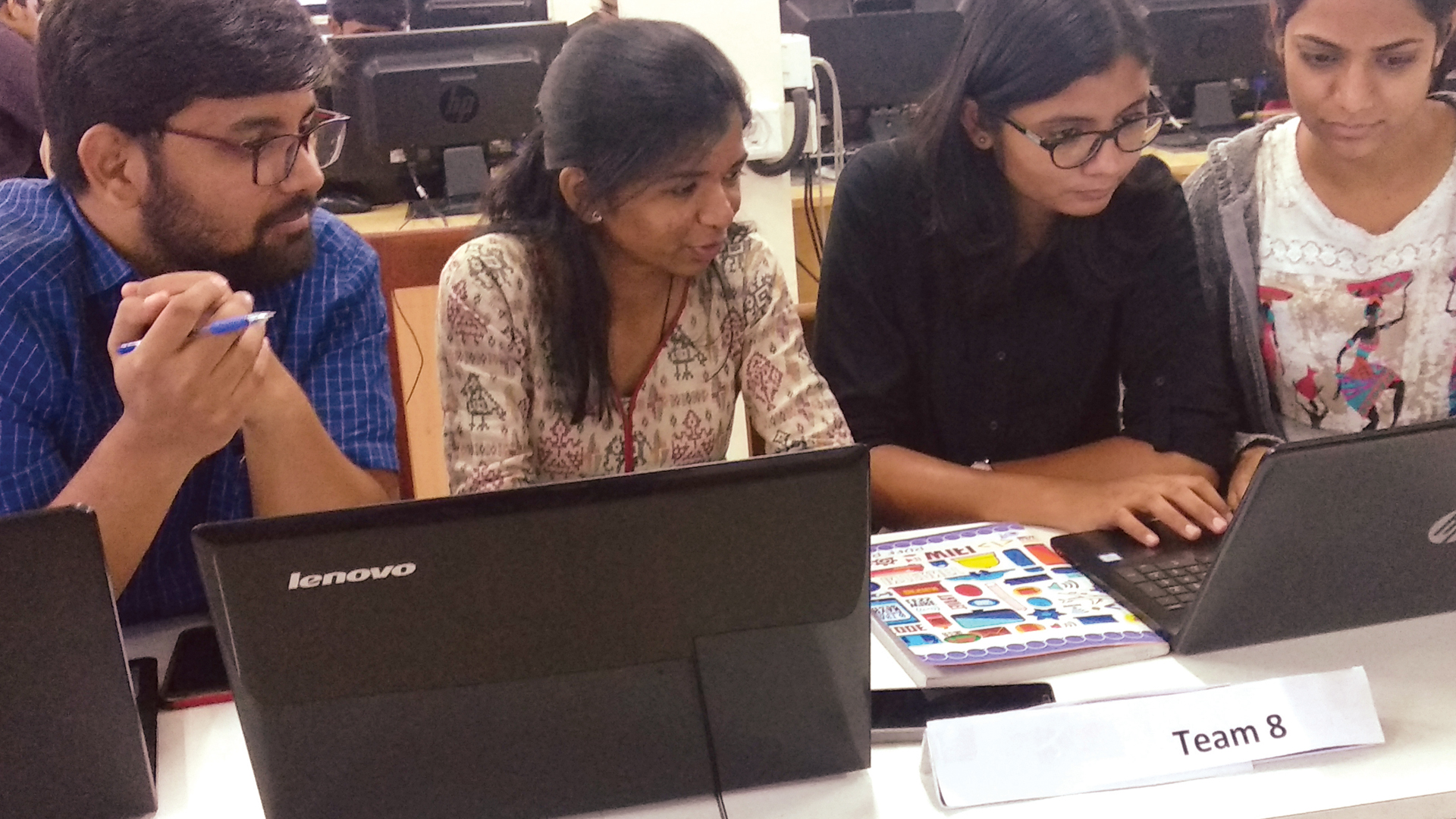

The acute need was for a bigger public-private ecosystem to smoothen the last mile for the platform, and for civic solutions to emerge from the data. The project solicited support to better understand how to take the platform forward and one answer was the ‘Pune open data hackathons’ — sessions comprising students, academia and private industry where participants compete to create solutions around a problem through the use of open data.

Dashboard for parents

The first such hackathon, held in January 2019, was with the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) and Symbiosis Institute. Participants were given the data sets on education and a problem statement. The goal was to create a dashboard for parents to access information on schools.

The hackathon led to Mr Shanbag’s remarkable school dashboard, with its GIS mapping of Pune schools and data visualisation features. It affirmed the fact that public-private data hackathons could generate useful applications. Since then, PMC and the Trusts have participated in several more hackathons that have led to promising results.

The Pune data genie is well and truly out of the bottle. What wishes can it grant? What good can it deliver? That part of the story is still unfolding and may lead to new discoveries over time. What PMC’s successful dance with data has already accomplished is make the city a torchbearer for urban India.

Data rush for denizens

How does open data benefit citizens? Here are some examples:

- Using its open data platform, the Pune Municipal Corporation (PMC) has geo-mapped postal pin codes to accurately indicate the lanes and houses that come under each ward in the city.

- Pune’s population figures varied widely but comparing election and census data has helped peg the figure at 4.3 million.

- Insights on air pollution came from correlating the number of vehicle registrations and the rise in pollution as reflected in Pune’s air quality index.

- An app that collates data on 4 million trees to shed light on areas with maximum green cover, places to find rare trees and those with medicinal properties, where to focus conservation efforts, the kind of trees that need to be planted, etc.

- A city health meter that collates ward-wise data using both positive figures (tree cover, number of hospitals, waste management services) and negative figures (air quality index, number of citizen’s grievances) to give Puneites a better idea of the areas they live in.

- An app that uses machine learning to analyse the language used by citizens posting grievances on Twitter and assigns these to the relevant PMC department.

An enabler like no other

Data mining may seem like an unusual venture, on the face of it, for a philanthropy such as the Tata Trusts. It is not, because, as Poornima Dore, programme head of the data-driven governance programme at the Trusts explains, transformation scenarios playing out across the world reveal the potential of harnessing data and technology for social development.

“There’s a lot of money that gets channelled into development, through government funds, the corporate social responsibility projects of companies and philanthropic organisations,” says Ms Dore. “We saw a strong role for data in improving service planning and decision making at the granular level, and with its use in enabling analyses of last-mile services and impact.”

The catch was the requirement: clarity on what kind of data, tools, processes and protocols are necessary at every level in the government hierarchy to help the system perform better.

With a vision to “activate rural and urban governance systems, including communities and associated stakeholders to move towards a data-reliant culture of decision making, and enhance the data and technology discourse in Indian governance,” the Data Driven Governance (DDG) portfolio at the Trusts aims to strengthen decision systems affecting development and planning, through the use of data and technology.

In the rural component, the Trusts have carried out extensive data collection drives and launched planning dashboards for select district administrations in Maharashtra, Odisha, Jharkhand and Andhra Pradesh. This was followed by a large-scale partnership with NITI Aayog, the policy think tank of the Indian government, for data collection and validation in 85 of India’s ‘aspirational’ districts using the DDG portfolio’s proprietary DELTA platform.

The DELTA platform and methodology has also been leveraged to build model Gram Panchayat Development Plans in 472 gram panchayats across five districts in the Jamshedpur Kalinganagar Development Corridor.

This has been done in partnership with Tata Steel Foundation.

In the urban space, the Trusts tied up with Canada-based World Council for City Data and PwC in 2016 to rank eight cities on quality of data collection and data capabilities. That led to the engagement with the Pune Municipal Corporation, a gargantuan institution with dozens of departments and thousands of employees providing services to millions of citizens and managing highly valuable infrastructure.

The Trusts' open data framework is a high-level guide for urban bodies on how information under 50-odd urban themes should be collected, cleaned, secured, standardised, updated and published.

The success of the Pune project has led to the Trusts collaborating with the Indian government’s Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs to define data strategies for the countrywide ‘smart cities mission’ and in developing capability-building processes for city data officers, a newly minted position.

“Data has a valuable role to play in helping civic systems perform better,” says Ms Dore. "The intent is to make urban systems more data savvy.

Previously published on Horizons, the Tata Trusts Magazine.