June 2025 | 1523 words | 6-minute read

The sprawling Chakan MIDC area in Maharashtra is home to some of the largest auto manufacturers in the world. As tens of thousands of workers stream through factory gates, contributing to the world’s fourth largest automotive sector, many remain invisible to the formal economy. Without proper documentation, excluded from social security schemes and public services, these workers, many of them migrants, are vulnerable to discrimination and exploitation.

“The pandemic brought to light the severe vulnerabilities faced by migrant and contract workers across the manufacturing sector,” says Arvind Goel, Vice Chairman, Tata AutoComp Systems (Tata AutoComp). “These workers — often the backbone of industrial operations — were left without access to essential services, social security, or reliable support systems during the crisis. As frontline relief efforts unfolded, it became clear that this wasn’t just a short-term emergency — systemic, long-standing barriers prevented these workers from accessing healthcare, documentation, financial services, and government welfare schemes.”

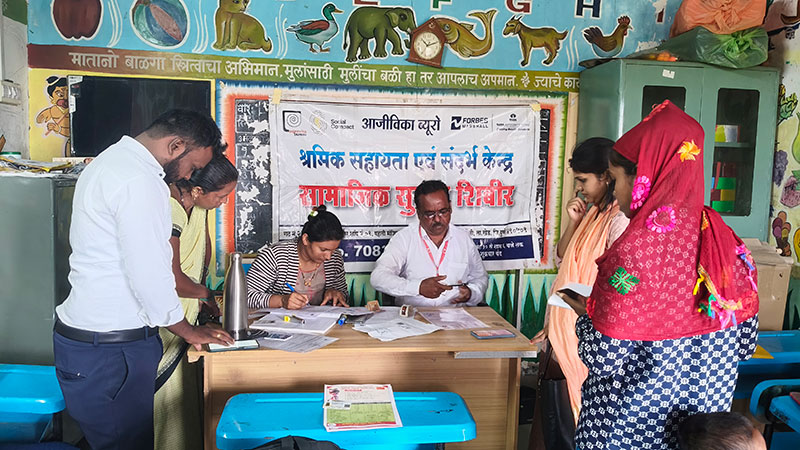

To address this inequality, Tata AutoComp established a Worker Facilitation Centre (WFC) in Chakan, in partnership with Forbes Marshall, an engineering company, and Aajeevika Bureau, non-profit organisation working on worker rights. Set up in 2021, the WFC represents a shift from traditional corporate social responsibility. It aims to tackle systemic issues that undermine worker welfare and address a pressing economic challenge — how to harness the productivity of this large informal force while ensuring dignity and rights for the individual.

The invisible economy

The Chakan MIDC industrial corridor has a vast number of migrant blue collar workers that are hired through contractors, paid in cash and excluded from the benefits that formal employment would provide. They come from rural areas in Maharashtra, Karnataka, Odisha and Uttar Pradesh, and lack the documentation or knowledge of how to navigate formal employment systems. They face challenges like less than minimum wages, unsafe working conditions, exploitation by middlemen, and unhygienic living conditions. Without proper identity documents they cannot access social security schemes, public services, healthcare, or financial services, like bank accounts. They have no access to legal aid when disputes arise at the workplace.

“It became clear that this wasn’t just a short-term emergency — systemic, long-standing barriers prevented these workers from accessing healthcare, documentation, financial services, and government welfare schemes.” - Arvind Goel, Vice Chairman, Tata Autocomp Systems

Located inside the industrial belt, the WFC serves as a resource hub and an advocacy centre for migrant workers across sectors in Chakan, stretching out to boundaries of Talegaon-Ambi, Ravet and Moshi. Open six days a week, the WFC has a five-member team that also works on two Sundays every month. On average, more than 150 workers visit the WFC every month, and, so far, the centre has helped ~11,300 workers — with 4,500+ assisted in FY25 alone. This is in addition to the thousands it has helped through regular health and tetanus vaccination camps, which also double as opportunities to educate workers on workplace safety and health.

To further enhance accessibility, mobile van services have been started, helping reach new migrant workers within a of 50 km radius every day. This initiative ensures timely support for workers who are otherwise difficult to reach through static infrastructure.

The development of Shramik Sarthis, workers who have benefited from the WFC and now act as ambassadors, has added another dimension of support. Shramik Sarthis have been trained to provide support and referrals, creating their own networks that extend the centre’s reach.

Realising rights

The centre’s services address the key barriers that prevent workers’ economic development. Among these is helping workers obtain identity documents like Aadhar, PAN, and ration cards. This seemingly basic service enables workers to open bank accounts, access related income and, public services, all of which have a profound impact on their incomes, health and safety. Additionally, the WFC holds awareness camps and builds financial inclusion with linkages to social welfare programmes that workers are very often unaware of. These include government-backed health, social security, pension, and life insurance schemes, as well as access to free or subsidised elementary, secondary and higher education for themselves and their families.

Strengthening protection

Migrant workers are especially vulnerable to wage theft, delayed or denied wage payments and workplace accidents, including burns, amputations, and electrocutions, which can at times prove fatal. Through its helpline India Labourline and network of paralegals and lawyers, the WFC provides free legal aid to workers, representing them in disputes and safeguarding their employment rights and interests. In FY25, the WFC’s mediations secured a ~Rs 31.5 lakh in unpaid wages, accident compensation and employer provident fund contributions for workers.

One of the largest settlements the WFC has worked on involved 83 migrant workers from rural Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh and Jharkhand. In December 2023, the WFC helped them file a case against their employer for unpaid Provident Fund (PF) dues — despite regular deductions from their salaries. With the WFC’s support, the workers received a total settlement of Rs 24,95,788 within six months. This timely resolution not only provided financial relief but also strengthened the workers’ trust in the WFC.

From exploitation to empowerment

Another important service is the on-the-job training (OJT) it offers workers, improving their employability and earning potential. Over 100 male and female workers have completed the OJT training so far. As part of the programme, the centre identifies experienced workers or contractors who act as trainers, providing technical as well as important life skills needed for growth. There are 45-day training courses for non-traditional livelihoods like masonry, motor winding, accounts tally and two-wheeler mechanic. On completion of the course, workers are awarded certificates and toolkits to help them in their new career.

Having a steady income, Sona, a participant in the On The Job masonry programme, says, has boosted her confidence, improved her family’s quality of life and enabled them to live with greater dignity.

The OJT masonry programme was a turning point for Sona*, a migrant from a rural village in Maharashtra, who lives with her husband and 13-year-old son. Today, Sona, earns an additional Rs 600 per day working in construction, building and plastering walls, tasks traditionally associated with men. Having a steady income, she shares, has boosted her confidence, improved her family’s quality of life and enabled them to live with greater dignity.

Extra push for women

About 25% of the centre’s beneficiaries are women and the WFC is looking to increase this number outreach activities in transit spots and community areas. It runs targeted awareness programmes on safety, sexual harassment and workplace rights, and offers specialised career counselling and financial literacy sessions for women. Efforts are made to ensure women access financial services, social programmes and government schemes using their own identity proofs and not those of their guardian/husband. This gives the women control over their economic resources, enhancing their financial independence.

Creating a safe space

For the centre to succeed in its mission, building and sustaining trust is crucial. “Building trust among workers — especially migrant or contract labourers who face systemic neglect — requires authentic engagement, credible partnerships, and peer-driven advocacy,” says Sudipta Marjit, Chief Human Resources Officer, Tata AutoComp. “Tata AutoComp’s employees actively volunteer their time and knowledge, conducting need assessments and safety trainings, and developing strategies to support the initiative. By engaging directly with workers, they demonstrate that the initiative is rooted in genuine care, not compliance. The partnership with Aajeevika Bureau adds another layer of credibility and neutrality.”

More than a help desk

The WFC’s role extends beyond support services to include research and policy advocacy. Aajeevika Bureau’s two-decade experience working with migrant workers helps in data collection and analysis, helping the WFC identify scalable interventions. Drawing from its field research, the WFC team has provided guidance to local and district administration on implementing the Building and Other Construction Workers scheme and the One Nation One Ration Card (ONOR) initiative on food security in the region.

“Tata AutoComp’s employees actively volunteer their time and knowledge, conducting need assessments and safety trainings, and developing strategies to support the initiative." - Sudipta Marjit, CHRO, Tata Autocomp Systems

“True success for the WFC goes far deeper than data,” says Mr Marjit. “It is also measured through qualitative impact and systemic change that reflect the human and social value of the initiative. It is seen when workers begin to advocate for their rights and approach public systems with confidence; when local leaders, influenced by the WFC, treat them as equals and not as outsiders.”

The path forward

In 2025, the WFC kickstarted its phase 2 activities — moving from providing foundational support to enabling long-term growth, empowerment, and mobility for workers. “This involves creating pathways for better income, job stability, and recognition, particularly for those in informal or contractual roles,” says Mr Marjit. “There is an increased focus on improving digital enablement and remote access to welfare schemes, entitlements, and grievance redressal support. The centre will also scale up the skilling and reskilling of women workers in areas that enhance employability and financial independence. Work is underway to align with formal government skill development programmes for certification and placement linkages for trained workers. The WFC has also identified a need to improve tracking of worker progress and obtaining feedback for real-time improvement.”

He explains that the long-term goal is to embed the WFC into the industrial and social ecosystem as a self-sustaining, scalable, and replicable model that can grow with minimal external intervention. “This vision is already taking shape in regions like Hadapsar and Pimpri-Chinchwad, where other corporates are adopting similar WFC models, demonstrating replicability and shared responsibility,” says Mr Marjit.

*Name changed on request

- Kermin Bhot