July 2025 | 999 words | 4-minute read

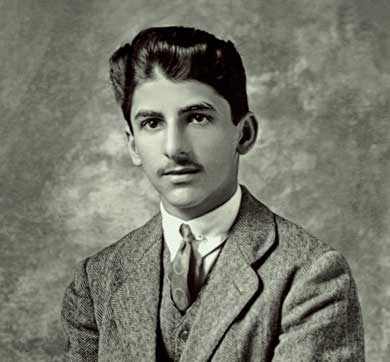

In the biography “Beyond the Last Blue Mountain” by R M Lala, JRD Tata recalls the time he had to leave India to join the French army as a conscript. An excerpt:

‘If I had to join the army, I wanted to pick the cavalry. I had seen polo matches in Bombay and Poona. Polo seemed a very exciting game and I thought maybe I could play polo later but first I had to learn to ride properly. So, when the time came to go into the army I pulled strings to join the cavalry, not too successfully as it turned out. My grandmother spoke to a General she knew. To my consternation, I was drafted in an Algerian regiment, an Arab regiment, where riding was very different from normal riding. You ride Arab horses—very exciting horses—on a different kind of saddle. This saddle had a pommel in front and if you jerked forward the pommel hit you in the plexus. If the horse galloped forward and you were not prepared for it, you lurched back where the rear saddle hit and bounced you forward, sometimes over the head of the horse.’

So, to his dismay, far from learning to ride well enough to play polo he was constantly anxious of being pierced by the high pommel in front or being catapulted over the head of the horse. ‘When riding you leaned forward in the saddle rubbing a part of the bottom different from the one on a European saddle. Within the first two days I had blisters. The Sergeant told me that when I got up in the morning I should go and sit in the horse trough. And for two days I did. It felt like fire but cured it.’

The regiment was called Le Spahis (The Sepoys) and was composed of Algerians, Tunisians, Moroccans and a few French; it was based in a dismal city called Vienne, south of Lyon. Brought up in luxury, Jehangir suddenly found himself with men from a totally different background. They were coarse in their manners and many of them were illiterate. Life in the barracks was pretty primitive. To his horror he discovered that most of his fellow soldiers never had a bath, save in summer. Jehangir was the odd man out because he went to a public bath once or twice a week. Many of the soldiers made fun of him for doing so.

Help came from an unexpected quarter. Jehangir’s Captain discovered that an educated prodigy who even knew typing had joined the unit. ‘The Captain, sporting the forbidding name of Massacrer, which in French literally means massacrer, promptly had me assigned as secretary in his office. One of the valued perquisites was that I did not have to get up at 5.30 in the morning to wash and groom my horse. The horse was ready for me. All I had to do was to climb the horse, sword in hand and exercise it. Another perk, so far as I was concerned, was that on my appointment to the good Captain’s office, I was transferred from my highly redolent dormitory to a storeroom which I shared with an old Arab veteran called Guelool, who, unfortunately, smoked and coughed all night. I later discovered that the real reason for this transfer from the dormitory was to keep me out of sight for fear that I might be pinched by a higher regimental officer. It did not take long for the Colonel to find out that the First Squadron had an educated prodigy, who could not only read and write French and English but could even type. I was then transferred, for the second time, to the relatively luxurious office of the Colonel, and a bed was provided for me in a back room where I was gloriously alone.

‘I became a favourite of officers applying for leave, whose applications I typed and who often graciously tipped me with a franc. During my year in the Spahis, I may have proved to be a good clerk, but I acquired little of military value for the possible defence of France. This was just 15 years before World War II broke out with its tanks and planes. We were given 6 rounds of ammunition, one live and five blanks. I fired a total of only 5 bullets. But I did learn to wield a sabre from horseback with reasonable proficiency. I remember feeling, and saying later, that if the Spahis were typical of France’s Army, she would lose the next war. It nearly happened.’

Jehangir discovered that at the end of the twelve-month period of conscription, the educated soldier who volunteered for an extension of six months could be assigned to an Officers Training Course and after that, was eligible to attend one of the world’s most famous riding schools at Saumur. ‘I decided to apply for a year’s extension of service. Fortunately, I had the good sense to consult my father,’ he says.

R.D. angrily turned down the proposal. Though upset, Jehangir bowed to parental guidance, little knowing at the time that his father’s decision would save his life. Shortly after he left for India, his squadron sailed to Morocco to fight the rebel chief, Abdel Karim. There it was ambushed and slaughtered to the last man, as the heroic garrison was in Beau Geste. In the normal course, after his twelve months in the army, Jehangir would have proceeded to Cambridge for his engineering degree. ‘But father decided that a college degree was not essential for a career in Tatas and summoned me to India. This decision is one I’ve regretted throughout my life and which caused me to have a long-lasting inferiority complex.’

On landing in India, Jehangir joined Tatas as an unpaid apprentice. It was December 1925.

Excerpted from 'Beyond the Last Blue Mountain' by RM Lala.